Posted by

Share this article

Time flies: over three years of Notifiable Data Breaches

On 22 February 2020, the OAIC marked the third-year anniversary of the enactment of the Privacy Amendment (Notifiable Data Breaches) Act 2017 (Cth), which introduced Part IIIC to the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) (Privacy Act).

Under Part IIIC, any organisation or agency the Privacy Act 1988 covers, must notify affected individuals and the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) when a data breach is likely to result in serious harm to an individual whose personal information is involved.

Further the OIAC website states that:

“A data breach occurs when personal information an organisation or agency holds is lost or subjected to unauthorised access or disclosure. For example, when:

- a device with a customer’s personal information is lost or stolen

- a database with personal information is hacked

- personal information is mistakenly given to the wrong person…”.

Whilst the OIAC’s statement may be well understood, a Bill currently with the New Zealand parliament to introduce a similar breach notification scheme, sheds further light on what may constitute a breach beyond what is currently being considered.

What’s notifiable? NZ explicitly takes a broader view

In the proposed New Zealand legislation, a breach not only includes Personally Identifiable Information (PII) disclosure, but also loss of access to the PII. The latter is not explicitly made in the Australian Act.

Under the New Zealand Bill Section 117(1), a “privacy breach” means:

- Any unauthorised or accidental access to, or disclosure, alteration, loss, or destruction of, the personal information; or

- An action that prevents the agency from accessing the information on either a temporary or permanent basis.

Is loss of access considered in Australian privacy law?

In contrast, the Australian Privacy Act, under Part II, makes no definitive definition. Instead the definition of a breach is made through a contrary statement, that is that it is a breach only if a set of conditions do NOT apply, leaving the definition of “breach” to be potentially wide, and consideration for loss of access to PII to be missed.

Part II states that a “breach”:

“a) in relation to an Australian Privacy Principle, has the meaning given by section 6A; and

- b) in relation to a registered APP code, has the meaning given by section 6B; and

- c) in relation to the registered CR code, has the meaning given by section 6BA.”.

When examining the respective codes, the reader finds the following:

“(1) For the purposes of this Act, an act or practice breaches an Australian Privacy Principle if, and only if, it is contrary to, or inconsistent with, that principle.

No breach–contracted service provider

(2) An act or practice does not breach an Australian Privacy Principle if:

(a) the act is done, or the practice is engaged in:

(i) by an organisation that is a contracted service provider for a Commonwealth contract (whether or not the organisation is a party to the contract); and

(ii) for the purposes of meeting (directly or indirectly) an obligation under the contract; and

(b) the act or practice is authorised by a provision of the contract that is inconsistent with the principle.”

and so on.

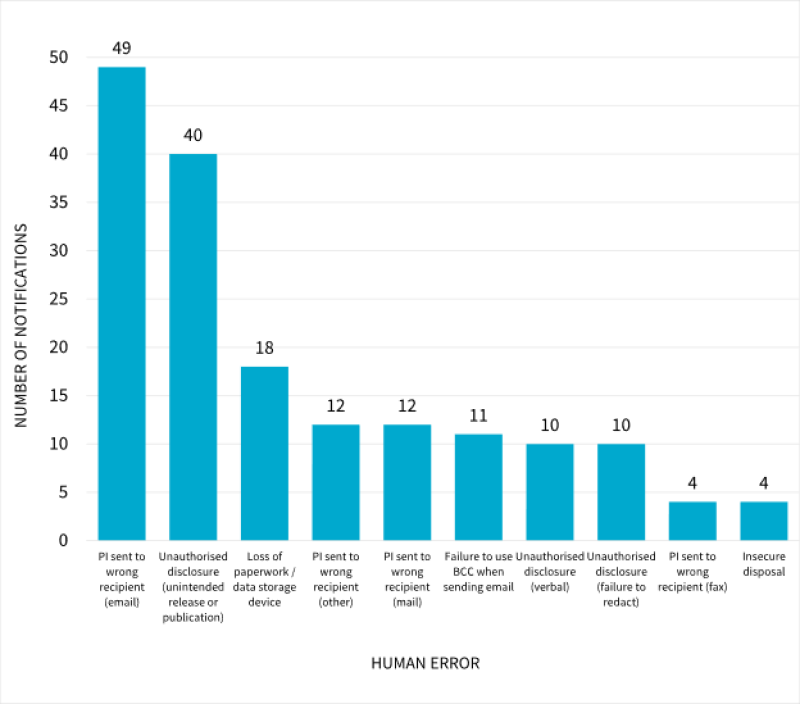

Adding to the lack of potential consideration for the loss of access to PII in the definition of a breach, the notifiable data breaches statistics published periodically by the OAIC provide details as to the nature of breaches, none of which typically include loss of access to PII.

The NZ legislation provides helpful guidance to all, even those only concerned with the Australian Privacy legislation, that serious harm can also be caused by the loss of access to PII.

For example, a health services entity may hold important PII about an individual that is paramount to providing time critical medical care and response. An aged care facility comes to mind for example. If access, even temporarily, to PII needed to treat the individual is lost, this may cause potential physical harm or even death. Note, that this loss of access may not be predicated on disclosure of the PII to unauthorised persons, and so may be otherwise deemed to be non-notifiable.

While definitively stated in the New Zealand Bill, the broad definition made in the Australian Act does not preclude this interpretation either.

What do you need to do?

Only time will tell how the Australian Commissioner, and the courts, treat Australian’s definition of a notifiable breach, and whether or not they will consider loss of accessto PII in due course.

Either way, it would be wise to ensure that your privacy controls and response plans consider the loss of access to PII also, not just disclosure to unauthorised persons.

The New Zealand Bill has gone through the Committee of Whole House on 3 June 2020, and is presently in the second last stage of accent (Third Reading) before being finalised by Royal Assent at some unknown time in the future. You can review the NZ parliament website to keep up to date with the pending Bill.

Contact us

Speak with a Thales Cyber Services ANZ

Security Specialist

Thales Cyber Services ANZ is a full-service cybersecurity and secure cloud services provider, partnering with clients from all industries and all levels of government. Let’s talk.